Learning CW

I started learning CW shortly after purchasing a Kenwood TS-530SP from a neighbor in the late 90s. I had my technician license and wanted to upgrade to get on HF. At that time, CW was part of each of the upgraded license classes.

Back then, before handheld cell phones were mainstream, let alone smartphones, I used a DOS program which would flash letters on the screen and then sound out the CW. It was a great program, and I had learned at least half the alphabet at 5 WPM.

CW Removed from Tests

After coming back into the hobby a few decades later, I was surprised to hear that CW was no longer part of the testing for the General and Extra exams. I’m sure there are some who feel this makes the tests too easy, or “lowers the bar” for getting on HF. Others would argue that the amateur radio service needs more licensees and more activity, in order to preserve the frequency allocations we have. Removing the CW requirement could bring more interest into the service. I tend to agree with both sides of that argument.

Tradition and History

If CW is no longer a requirement for upgrading to General or Extra class, then why learn it? When I got into the hobby when I did, in the 90s, CW was a requirement for anything above Technician class. As a result, most amateurs knew CW. Not knowing it felt like I was missing a big part of the hobby. CW was one of the first modes of radio communication. Why not learn and experience the same mode of communication that so many have done before?

When All Else Fails

In addition to tradition, history, and participation in a very common form of making contacts, CW can also be something you learn for emergency communication or when other forms of communication aren’t possible or available. It would be rather unlikely or extreme if internet, cell service, and all other forms of communication became unavailable for an extended period of time. But, having the knowledge to build your own CW transmitter and receiver and to be able to copy is a good skill to have. It’s more likely that a DX contact by CW would be possible compared to phone given the same band conditions. CW is less affected by noise, and therefore all else being equal, you’re more likely to make a DX contact by CW compared to phone.

Picking it up Again

Using the Ham Morse app I was surprised at how quickly I was able to catch back up. My routine was to listen to 10-20 minutes of CW on the app daily, and also to listen to slow CW on HF if I could find it. I found that actually sitting down and writing down what I heard would help retain the progress I made.

Keys and Paddles

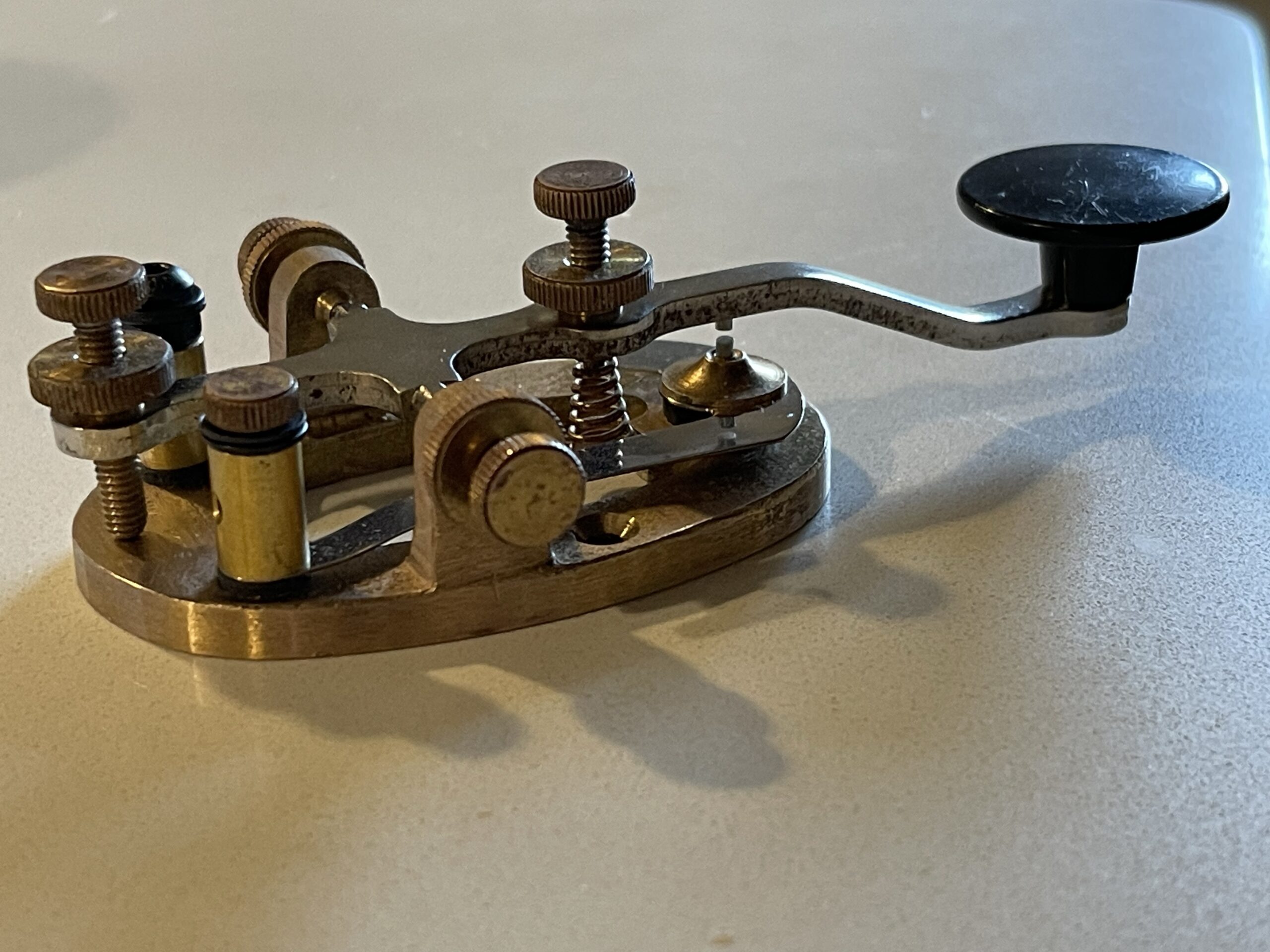

I’m taking the advice of many who recommend learning with a straight key before using the paddles.

The key I’m using is from EF Johnson. They key came from N1QQV (sk). It looked quite old, and I noticed the stamp toward the back of the key. After cleaning it, I was able to read the marking. Interestingly, the company is now owned by JVCKenwood. I’m not sure if this key was an accessory sold by Kenwood at some point, since the key came with the Kenwood TS-530SP I bought from N1QQV. The style of the key is very similar to the J-38 from WWII.

Listening to CW on HF

A big part of learning CW in my opinion is hearing it live and picking out as much as you can copy. Regardless of the speed, learning the skill and experience of hearing interference and adjacent signals is necessary. You will likely not have perfect band conditions on your first QSO let alone most QSOs. You should be familiar with basic concepts for tuning up for a CW contact if you’re responding to a CQ for example, using the zero beat method if your radio doesn’t auto tune the VFO.

Also, almost all modern radios will have features to help with CW mode in a crowded area of the band. For example, if your radio has a CW mode, it will likely be a much more narrow receive mode than phone. Your rig may have an even more narrow CW filter. This will help keep adjacent signals above and below your VFO frequency attenuated or eliminated. If you’ve ever heard several CW signals at the same time, you’ll appreciate the narrow filtering available on modern rigs. If you haven’t experienced this, try listening to the CW portion of the popular HF bands when your rig is in SSB mode. It won’t take long for you to find a spot where you can hear several stations at the same time. Then switch to CW mode and/or narrow filtering mode to see how to hone in on just one of those signals.

Lastly, if you’ve ever been on HF and heard a steady tone from either an AM carrier or other source of RFI, be familiar with your notch filter, if your radio has one. The notch filter can also be used to notch out an adjacent CW signal. Try using the notch filter to block out a CW signal. Or, tune to a position on the band where a constant pitch can be heard. Then experiment with the notch filter to try to block it out.

Becoming familiar with your radio’s filtering abilities will help you copy CW when conditions are less than ideal. You won’t likely have a crisp clean signal to hear when live on the air like you do with CW learning tools.

If you’re familiar with these features or you have just experimented with them for the first time, by now you might appreciate the older rigs which didn’t have menus – they had dedicated switches and dials for each of these features. Almost all of the entry level radios will have menus you’ll need to memorize to get to these features quickly. The older rigs and contest rigs will have dedicated buttons and dials for these commonly used features.

Perseverance

I plan to keep at it to the very first QSO on HF. The challenge to learning CW is a matter of dedicating a small amount of time daily to practice.